Poetry is a powerful means of self expression, and your truth can be expressed in poetry in a unique way. Poetry is not as popular as it deserves to be, perhaps because it is so mangled in our schools, and although many people enjoy song lyrics, often what passes for poetry is doggerel, meaning trivial, cheap and relying on obvious “poetical” devices such as overdone rhythm and rhyme. However, there is something to be found in poetry that is not often found elsewhere, a deft expression in words of something that lies on the very edge of our understanding.

Poetry is a powerful means of self expression, and your truth can be expressed in poetry in a unique way. Poetry is not as popular as it deserves to be, perhaps because it is so mangled in our schools, and although many people enjoy song lyrics, often what passes for poetry is doggerel, meaning trivial, cheap and relying on obvious “poetical” devices such as overdone rhythm and rhyme. However, there is something to be found in poetry that is not often found elsewhere, a deft expression in words of something that lies on the very edge of our understanding.

Take this fragment by William Carlos Williams:

“I come, my sweet, to sing to you!

My heart rouses thinking to bring you news of something

that concerns you

and concerns many men. Look at what passes for the new.

you will not find it there but in

despised poems. It is difficult

to get the news from poems

yet men die miserably every day

for lack

of what is found there.

Hear me out

for I too am

concerned

and every man who wants to die at peace in his bed

besides.

(William Carlos Williams, 1883-1963, Asphodel, That Greeny Flower, 1962). This poem is copyright and can only be used for purposes of personal study.

I think we can all understand something of what he means by what is found in despised poems and not in the news of the day… even though he does not explicitly state what this is, and only implies it, obliquely. He gets close to complaining about the state of the news of the world, but this is a poem and not a rant. He lifts an ordinary complaint – about how the news does not recognise the poetry in life – into a poem that can be universally understood by anyone, anywhere, at any time.

So what is found there, in the realm of poetry?

So what is found there, in the realm of poetry?

Here are some of my thoughts, and you may also have further ones of your own:

*Our interconnectedness with all states of being. As the Welsh bards tend to say, “I have been the rabbit, the mountain, the hunter and the hunted”, not “I have seen” them.

*Valuing the truth of the imagination rather than scorning it

*Your personal truth, and your witness to this, your honouring of your truth

*Questioning some fundamental assumptions about consensual reality that are taken for granted but that you do not agree with

*A place where your acute and subtle sensitivity, so often ignored or crushed in the world, can be accepted and valued

*A place to celebrate love and beauty, or anything

*A way to write a full response to an event,

What is a poem?

A poem is news from another world, a different perspective, a different world where different rules apply. This world can be unique, strange, hideous or beautiful, and operates by completely different rules and laws. The normal assumptions we make (such as the facts of gravity) do not have to apply. A poem is an expression of some power within that wants to flow through you; it’s in the excitement, passion or danger you feel when you want to express something that is just at the edge of your capacity to understand or describe it. Poetry is a like a narrow path around the edges of your perception, and somehow you have to get the reader to agree to come with you on this perilous trip.

How can you as a journal writer add poetry, or poetic devices, to your journal writing?

If you love poetry, poetry belongs to you in your everyday life and need not be left in the dusty pages of your household anthology that no one reads. By entering a state of poetry in your journal writing you can extend your creative flow and claim your own access to poetic voice.

Some guidelines to get you started writing poems in your journal

Some guidelines to get you started writing poems in your journal

Your job is to faithfully present the world of the poem in as few words as possible. In a poem, as in an advert, words are expensive, and every single word that is not necessary should be edited out. You may need extra words for scaffolding at the beginning which you remove once your poem is revealed.

So you can forget wasting time with introductions and beginning sentences properly, or explaining anything about how we got here. However you can anchor a poem well by using some evocative details of location, season, light, time period, and so forth.

Many poets do not know what their poem is going to be “about” before they start, and might never be able to tell you. So you do not need to do this, and you never need to explain to anyone what it is about. Saying to yourself “I am going to write a poem about a giraffe” may not result in much. However, show us a glimpse of your giraffe resting at the edge of a dark forest and we are going to be fascinated.

Show, not tell. This means do not go into narrative story-telling mode where you describe or talk about your subject matter, unless you are a deft story teller and you are sure of what you are doing. Your job is to bring the reader and yourself into your poem world, a mysterious world where everything follows its own laws. Think of just how much can be evoked in a three line haiku, or these few lines from Emily Dickinson, where she is talking about the oppressive, closed-in feeling of her life on winter afternoons. She doesn’t give any context except season and light and she conveys to us that she feels shut in and despairing in such a way that we can really feel something similar.

There’s a certain Slant of light,

Winter Afternoons –

That oppresses, like the Heft

Of Cathedral Tunes –

Heavenly Hurt, it gives us –

We can find no scar,

But internal difference –

Where the Meanings, are –

None may teach it – Any –

’Tis the seal Despair –

An imperial affliction

Sent us of the Air –

When it comes, the Landscape listens –

Shadows – hold their breath –

When it goes, ’tis like the Distance

On the look of Death –

(Any complete works of Emily Dickinson will include this poem and her work is easily available as it is out of copyright)

The laws of your poem world can include, for example, reversals (a tiny elephant and an enormous baby), exaggerate or minimise, or change the laws of physics.

What does a person in this world see, feel, hear, taste, and smell? What happens in their inner world?

Imagery and synonyms are your friends. Language and words are your friends.

Incongruity is also your friend. Bring things together that until now have always been separate, such as the bee and the oyster. Show their intrinsic connection.

Include the emotional truth. This does not have to include literal, factual points, or it can if you want it to.

Address your reader directly. Make your poem direct, and not passive. Reading the poem should be an experience in itself, rather than an iteration of an experience that you had.

You have got to grab the reader’s attention in the first few words. Poetry used to be intended to be recited or performed, not read silently from the page. Read your work aloud to ensure it sounds good and is fresh and engaging. Reading it aloud will help you quickly identify any lines that feel off.

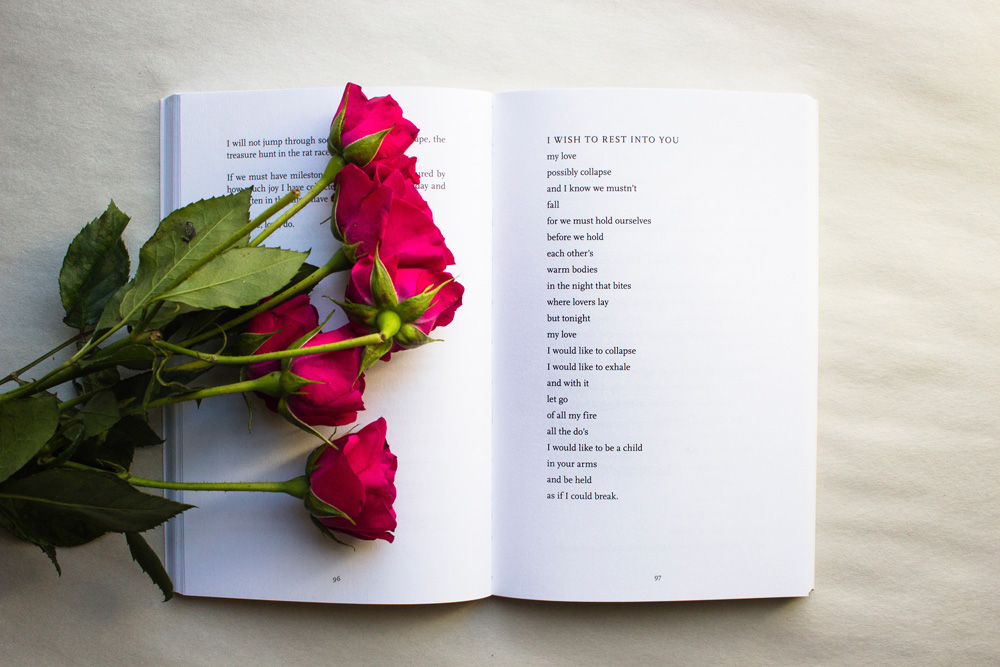

A poet reads poetry and does not just write it. Let your poetry be a response and dialogue with the work of other poets.

When you want to create your own unique world in your journal, poetry can be an important part of this. Think of “what is found there”, the unique sensitivity, experience and understanding that only you possess.

What not to do:

What not to do:

Stay away from generalisations about the state of the world, or abstract philosophical statements. Don’t make overt philosophical generalisations unless you are very confident your poem is strong enough to hold them.

Avoid ranting and complaining unless you do it in an exaggerated form

Don’t preach or harangue the reader to agree with your point of view They already know about the rainforests. What can you bring to this table that is fresh and new?

If you have a tired and well worn theme then look at it “slant” as Emily Dickinson would say.

Don’t explain, justify or interpret. Don’t tell the reader how to interpret the data. Trust them to have the ability to do this for themselves. Tell them that the house burned down with a child in it, but don’t tell them to feel sorry for the child. Make it more bare because by what you leave out, you can make the poem much more visceral and powerful

Poetic devices

Often the use of poetic devices, such as rhyme, meter, line breaks, poetic forms or alliteration are assumed to be what turns words into poems. It is not so. A poet, like a musician, must work with all these elements as tools, but they are not the poem itself any more than notes, rhythm and instruments are in themselves music.

Voice and point of view

You can write in any voice and be anyone or anything, from any viewpoint. This can immediately help you see things fresh and new, for example experience your room as the spider under the chair. Voice also includes the tone and attitude of the poem, such as jaded and worldly wise.

Repetition

A poetic device that has surprising power, as in stanza repeats, word repeats, or rhyme repeats.

Rhyme

Go steady with this, as it is vastly overused. Half rhymes can be more effective. Rhymes that are insistent and too obvious have an amateur feel, like you are being too enthusiastic, and it is just not cool! They work better in song than in modern poetry.

Meter

The rhythm of the poem must work when it is read aloud. This is about where you place the stress, as well as the number of syllables in a line. There are many different metric forms, such as the over-used iambic pentameter, said to replicate the rhythm of a person walking.

Line breaks

Use your line breaks to create dramatic effects, or to help the poem flow. If you experiment with chopping a piece of prose up with line breaks, you can find out some interesting ways to use them. If a word is to be emphasised, then where you put it on the line is important.

Poetic forms

Examples are free verse, the sonnet, the villanelle, the pantoum, the ghazal, the haiku and any form you can set yourself, such as four line stanzas with an a/b, a/b rhyme scheme like a ballad. It can be a good discipline to make your poem into one of these, as by having to fit into the form you have to hone your work and make creative choices you would not have considered otherwise. You can find the rules of each form in any poetry manual, or invent your own.

Visual shape

Some poems rely on the shape of the lines on the page, for example wings, or words dotted about, and this can be very effective in a journal, whether or not you also combine this with art elements.

Poetry prompts to try in your journal

Write a list of random words. For example collect some from a technical manual, some from a novel and some from a newspaper. Find different ways to connect them together in a poem.

Write a response to something that uplifts you. Listen to inspiring music, for example, and write down words about how it makes you feel and what it makes you think about. Write a response to another poem, a painting, or anything at all. If you find another poem you really love, steal the bit you love and use it as a starting point and build your own poem around it. (Don’t publish it with a large chunk of someone else’s poem in it).

“Translate” poems or texts written in a foreign language that you only partially understand, and make your own poems from this.

Open several books or magazines at a random page, copy out a selected fragment or a few words, and collect them into a poem.

Become a butterfly or moth collector, collecting words that come to you, that just appear, unexpectedly, whether in a conversation, on the radio, or in any chance encounter. Write down and keep words and phrases that excite you in a list form and see how you find the connections between them. It’s good to keep a pocket journal with you always, a butterfly journal so that these lovely words and ideas do not escape and become instantly forgotten.